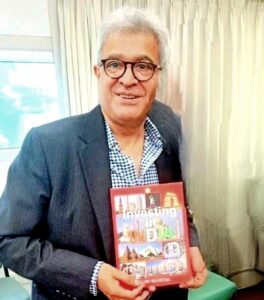

Jawhar Sircar : (Member : Rajya Sabha.) 11th. October, 2021. Now that Pujas are almost here, and Corona notwithstanding, millions of Bengalis will hop from pandal to pandal — a few questions may be interesting.

Have we ever wondered why Durga appears with her four children only in Bengal — and no where else in India? Or why the children do not help their mother in her life and death battle? In fact, they look away from the deadly struggle.

If Durga is really a loving daughter who returns to her parents’ home for just four days every year, then why is she dressed for war? And, why does she need to drag a half dead, bleeding Mahishasura to her mother?

These contradictions were, in fact, noticed by the 19th century poet, Dasharathi Ray. In his poem, Menaka screams:

“Oh, Giri! Where is my daughter, Uma?

Who have you brought into my courtyard?

Who is this ferocious female warrior?”

Rashikchandra Ray also echoes Menaka’s sentiment:

“ Giri, who is this woman in my house?

She cannot be my darling Uma.”

But, we must also realise that without her battle dress and the scene of her do-or-die struggle with Mahishasura, she would not be recognised as Durga the victorious goddess. She represents power and the zamindars of Bengal who started the public worship of Durga in the 17th and 18th century needed to demonstrate their own power to the peasants. Farmers were a fickle lot then and often deserted their zamindaris if their terms did not suit them or there was a famine.

This was also when the new entrepreneurial class of zamindars were extending cultivation of more productive Aman rice in lieu of traditional Aus. Aman needed more water and the low-lying wetlands of the Bengal delta were colonised but only after the buffaloes who infested these area were driven out or killed. Durga was invoked as the slayer of the Mahishasura, the buffalo demon — who was carried all the way to Giri and Menaka.

The four children were a bit of a problem. The common folk already had a ferocious mother — Kali — and now insisted on worshiping a good ‘mother’ with a happy ‘family’. Incidentally, Kartik and Ganesh had emerged as independent gods who had their own long histories of evolution from non-Aryan culture. The former arose from the Dravidian tradition of Murugan, Aramugam, Senthil or Subhramania, where he is a pre-puberty boy-god (not a virile adult). Ganesh or gana-eesha, god of the short, ugly ganas surely emerged from indigenous roots.

They were converted into Durga’s sons by the Skanda Purana of Tamil country and the Shiva Purana. The two made their first ‘guest appearance’ in Bengal, standing next to Durga, in the 12th century icons found at Nao-Gaon in Rajshahi and in Comilla’s Dakshin Muhhamadpur. Their presence is understandable but the Puranas gave them no role in the war against Mahishasura, so they are simply ‘add-ons’ in Bengal with nothing to do.

But Lakshmi and Saraswati were more problematic, because as Vishnu’s consort, Sri or Lakshmi is actually ‘older’ than Durga. Saraswati appears in the Vedas and was already known as Brahma’s wife. Eventually, under pressure from the Bengali masses, all four went through age reduction to qualify as Durga’s children. The two daughters don’t even have proper adoption certificates and no role to play — as no new Puranas were written after the 14th century.

At the same time, patriarchal Brahmanism was actually relieved to ‘domesticate‘ the warrior goddess as a loving mother and a daughter.

Such fiercely independent goddess could give other women wrong notions of autonomy and what is feminine. They felt it was safer to bind down the independent warrior goddess to her home, now that she had four children.

Such fiercely independent goddess could give other women wrong notions of autonomy and what is feminine. They felt it was safer to bind down the independent warrior goddess to her home, now that she had four children.

Thus we have this imagery only in Bengal.

Be First to Comment